An unknown Chinese-speaking threat actor has been attributed to a new kind of sophisticated UEFI firmware rootkit called CosmicStrand.

“The rootkit is located in the firmware images of Gigabyte or ASUS motherboards, and we noticed that all these images are related to designs using the H81 chipset,” Kaspersky researchers said in a new report published today. “This suggests that a common vulnerability may exist that allowed the attackers to inject their rootkit into the firmware’s image.”

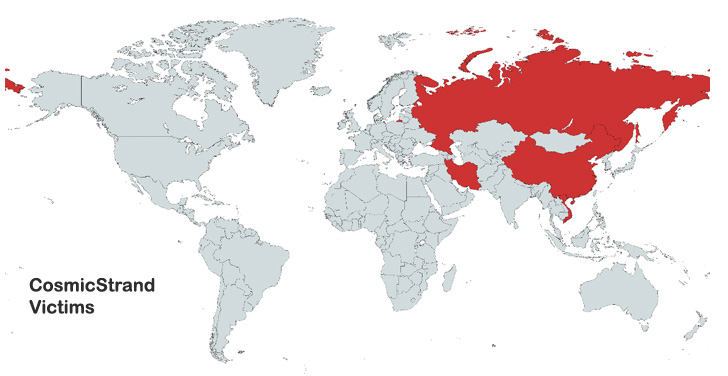

Victims identified are said to be private individuals located in China, Vietnam, Iran, and Russia, with no discernible ties to any organization or industry vertical. The attribution to a Chinese-speaking threat actor stems from code overlaps between CosmicStrand and other malware such as the MyKings botnet and MoonBounce.

Rootkits, which are malware implants that are capable of embedding themselves in the deepest layers of the operating system, are morphed from a rarity to an increasingly common occurrence in the threat landscape, equipping threat actors with stealth and persistence for extended periods of time.

Such types of malware “ensure a computer remains in an infected state even if the operating system is reinstalled or the user replaces the machine’s hard drive entirely,” the researchers said.

CosmicStrand, a mere 96.84KB file, is also the second strain of UEFI rootkit to be discovered this year after MoonBounce in January 2022, which was deployed as part of a targeted espionage campaign by the China-linked advanced persistent threat group (APT41) known as Winnti.

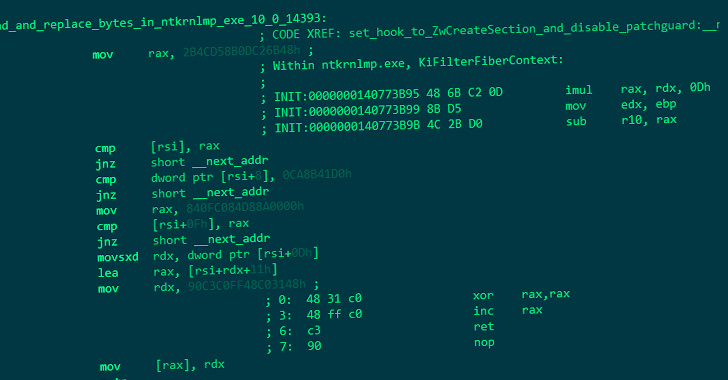

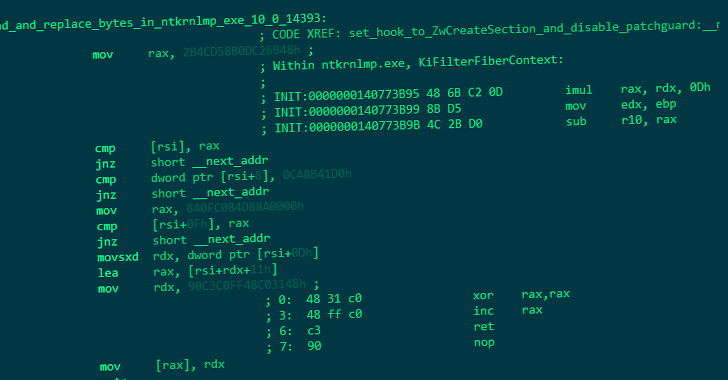

Although the initial access vector of the infections is something of a mystery, the post-compromise actions involve introducing changes to a driver called CSMCORE DXE to redirect code execution to a piece of attacker-controlled segment designed to be run during system startup, ultimately leading to the deployment of a malware inside Windows.

In other words, the goal of the attack is to tamper with the OS loading process to deploy a kernel-level implant into a Windows machine every time it’s booted, using this entrenched access to launch shellcode that connects to a remote server to fetch the actual malicious payload to be executed on the system.

The exact nature of the next-stage malware received from the server is unclear as yet. What’s known is that this payload is retrieved from “update.bokts[.]com” as a series of packets containing 528 byte-data that’s subsequently reassembled and interpreted as shellcode.

The “shellcodes received from the [command-and-control] server might be stagers for attacker-supplied PE executables, and it is very likely that many more exist,” Kaspersky noted, adding it found a total of two versions of the rootkit, one which was used between the end of 2016 and mid-2017, and the latest variant, which was active in 2020.

Interestingly, Chinese cybersecurity vendor Qihoo360, which shed light on the early version of the rootkit in 2017, raised the possibility that the code modifications may have been the result of a backdoored motherboard obtained from a second-hand reseller.

“The most striking aspect […] is that this UEFI implant seems to have been used in the wild since the end of 2016 – long before UEFI attacks started being publicly described,” the researchers said. “This discovery begs a final question: if this is what the attackers were using back then, what are they using today?”