Targeted attacks

New technique for installing fileless malware

Earlier this year, we discovered a malicious campaign that employed a new technique for installing fileless malware on target machines by injecting a shellcode directly into Windows event logs. The attackers were using this to hide a last-stage Trojan in the file system.

The attack starts by driving targets to a legitimate website and tricking them into downloading a compressed RAR file that is booby-trapped with the network penetration testing tools Cobalt Strike and SilentBreak. The attackers use these tools to inject code into any process of their choosing. They inject the malware directly into the system memory, leaving no artifacts on the local drive that might alert traditional signature-based security and forensics tools. While fileless malware is nothing new, the way the encrypted shellcode containing the malicious payload is embedded into Windows event logs is.

The code is unique, with no similarities to known malware, so it is unclear who is behind the attack.

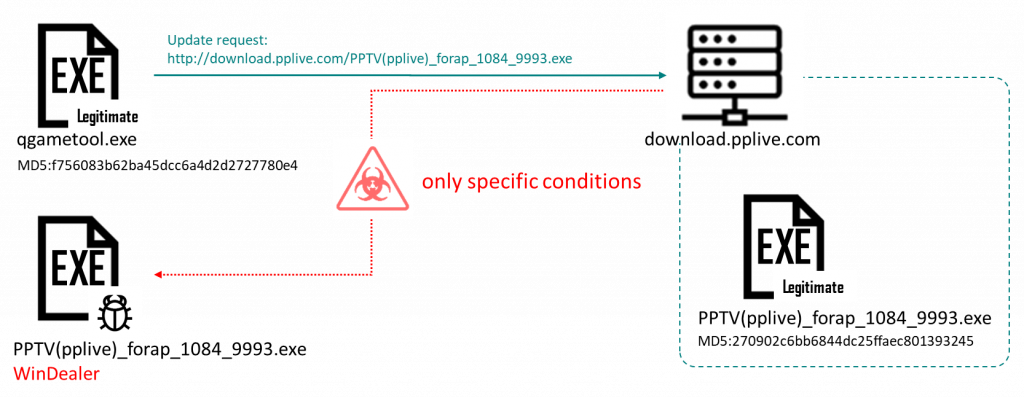

WinDealer’s man-on-the-side spyware

We recently published our analysis of WinDealer: malware developed by the LuoYu APT threat actor. One of the most interesting aspects of this campaign is the group’s use of a man-on-the-side attack to deliver malware and control compromised computers. A man-on-the-side attack implies that the attacker is able to control the communication channel, allowing them to read the traffic and inject arbitrary messages into normal data exchange. In the case of WinDealer, the attackers intercepted an update request from completely legitimate software and swapped the update file with a weaponized one.

The malware does not contain the exact address of the C2 (command-and-control) server, making it harder for security researchers to find it. Instead, it tries to access a random IP address from a predefined range. The attackers then intercept the request and respond to it. To do this, they need constant access to the routers of the entire subnet, or to some advanced tools at ISP level.

The vast majority of WinDealer’s targets are located in China: foreign diplomatic organizations, members of the academic community, or companies active in the defense, logistics or telecoms sectors. Sometimes, though, the LuoYu APT group will infect targets in other countries: Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, India, Russia and the US. In recent months, they have also become more interested in businesses located in other East Asian countries and their China-based offices.

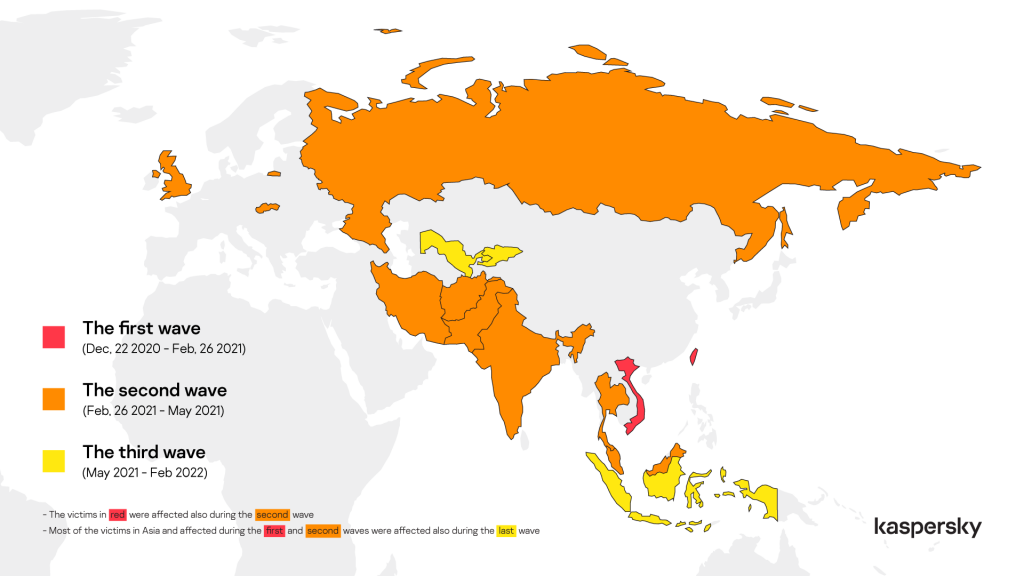

ToddyCat: previously unknown threat actor attacks high-profile organizations in Europe and Asia

In June, we published our analysis of ToddyCat, a relatively new APT threat actor that we have not been able to link to any other known actors. The first wave of attacks, against a limited number of servers in Taiwan and Vietnam, targeted Microsoft Exchange servers, which the threat actor compromised with Samurai, a sophisticated passive backdoor that typically works via ports 80 and 443. The malware allows arbitrary C# code execution and is used alongside multiple modules that let the attacker administer the remote system and move laterally within the targeted network. In certain cases, the attackers have used the Samurai backdoor to launch another sophisticated malicious program, which we dubbed Ninja. This is probably a component of an unknown post-exploitation toolkit exclusively used by ToddyCat.

The next wave saw a sudden surge in attacks, as the threat actor began abusing the ProxyLogon vulnerability to target organizations in multiple countries, including Iran, India, Malaysia, Slovakia, Russia and the UK.

Subsequently, we observed other variants and campaigns, which we attributed to the same group. In addition to affecting most of the previously mentioned countries, the threat actor targeted military and government organizations in Indonesia, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. The attack surface in the third wave was extended to desktop systems.

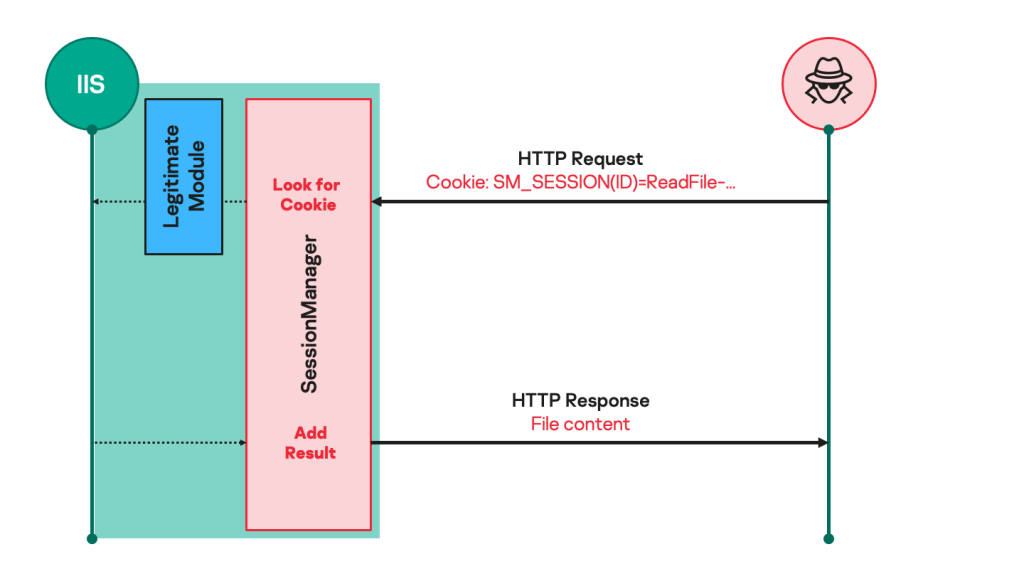

SessionManager IIS backdoor

In 2021, we observed a trend among certain threat actors for deploying a backdoor within IIS after exploiting one of the ProxyLogon-type vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange. Dropping an IIS module as a backdoor enables threat actors to maintain persistent, update-resistant and relatively stealthy access to the IT infrastructure of a target organization — to collect emails, update further malicious access or clandestinely manage compromised servers.

We published our analysis of one such IIS backdoor, called Owowa, last year. Early this year, we investigated another, SessionManager. Developed in C++, SessionManager is a malicious native-code IIS module. The attackers’ aim is for it to be loaded by some IIS applications, to process legitimate HTTP requests that are continuously sent to the server. This kind of malicious modules usually expects seemingly legitimate but specifically crafted HTTP requests from their operators, triggers actions based on the operators’ hidden instructions and then transparently passes the request to the server for it to be processed just as any other request.

As a result, these modules are not easily spotted through common monitoring practices.

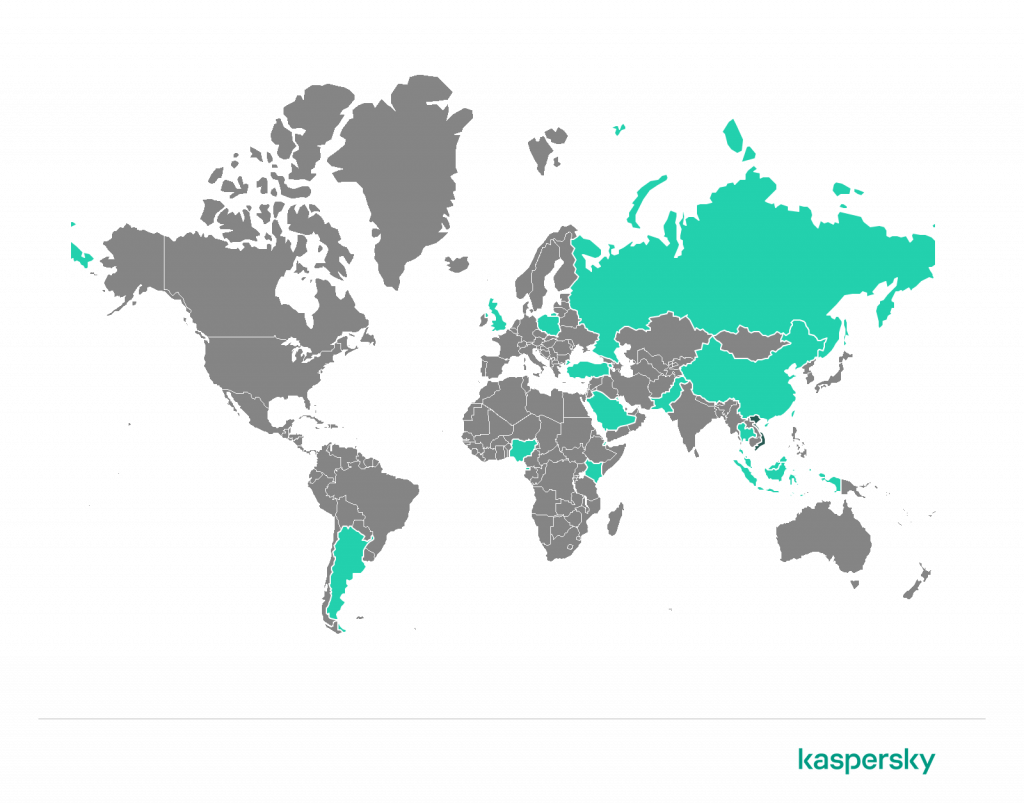

SessionManager has been used to target NGOs and government organizations in Africa, South America, Asia, Europe and the Middle East.

We believe that this malicious IIS module may have been used by the GELSEMIUM threat actor, because of similar victim profiles and the use of a common OwlProxy variant.

Other malware

Spring4Shell

Late in March, researchers discovered a critical vulnerability (CVE-2022-22965) in Spring, an open-source framework for the Java platform. This is a Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerability, allowing an attacker to execute malicious code remotely on an unpatched computer. The vulnerability affects the Spring MVC and Spring WebFlux applications running under version 9 or later of the Java Development Kit. By analogy with the well-known Log4Shell vulnerability, this one was dubbed “Spring4Shell”.

By the time researchers had reported it to VMware, a proof-of-concept exploit had already appeared on GitHub. It was quickly removed, but it is unlikely that cybercriminals would have failed to notice such a potentially dangerous vulnerability.

You can find more details, including appropriate mitigation steps, in our blog post.

Actively exploited vulnerability in Windows

Among the vulnerabilities fixed in May’s “Patch Tuesday” update was one that has been actively exploited in the wild. The Windows LSA (Local Security Authority) Spoofing Vulnerability (CVE-2022-26925) is not considered critical per se. However, when the vulnerability is used in a New Technology LAN Manager (NTLM) relay attack, the combined CVSSv3 score for the attack-chain is 9.8. The vulnerability, which allows an unauthenticated attacker to force domain controllers to authenticate with an attacker’s server using NTLM, was already being exploited in the wild as a zero-day, making it a priority to patch it.

Follina vulnerability in MSDT

At the end of May, researchers with the nao_sec team reported a new zero-day vulnerability in MSDT (the Microsoft Support Diagnostic Tool) that can be exploited using a malicious Microsoft Office document. The vulnerability, which has been designated as CVE-2022-30190 and has also been dubbed “Follina”, affects all operating systems in the Windows family, both for desktops and servers.

MSDT is used to collect diagnostic information and send it to Microsoft when something goes wrong with Windows. It can be called up from other applications via the special MSDT URL protocol; and an attacker can run arbitrary code with the privileges of the application that called up the MSD: in this case, the permissions of the user who opened the malicious document.

Kaspersky has observed attempts to exploit this vulnerability in the wild; and we would expect to see more in the future, including ransomware attacks and data breaches.

BlackCat: a new ransomware gang

It was only a matter of time before another ransomware group filled the gap left by REvil and BlackMatter shutting down operations. Last December, advertisements for the services of the ALPHV group, also known as BlackCat, appeared on hacker forums, claiming that the group had learned from the errors of their predecessors and created an improved version of the malware.

The BlackCat creators use the ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) model. They provide other attackers with access to their infrastructure and malicious code in exchange for a cut of the ransom. BlackCat gang members are probably also responsible for negotiating with victims. This is one reason why BlackCat has gained momentum so quickly: all that a “franchisee” has to do is obtain access to the target network.

The group’s arsenal comprises several elements. One is the cryptor. This is written in the Rust language, allowing the attackers to create a cross-platform tool with versions of the malware that work both in Windows and Linux environments. Another is the Fendr utility (also known as ExMatter), used to exfiltrate data from the infected infrastructure. The use of this tool suggests that BlackCat may simply be a re-branding of the BlackMatter faction, since that was the only known gang to use the tool. Other tools include the PsExec tool, used for lateral movement on the victim’s network; Mimikatz, the well-known hacker software; and the Nirsoft software, used to extract network passwords.

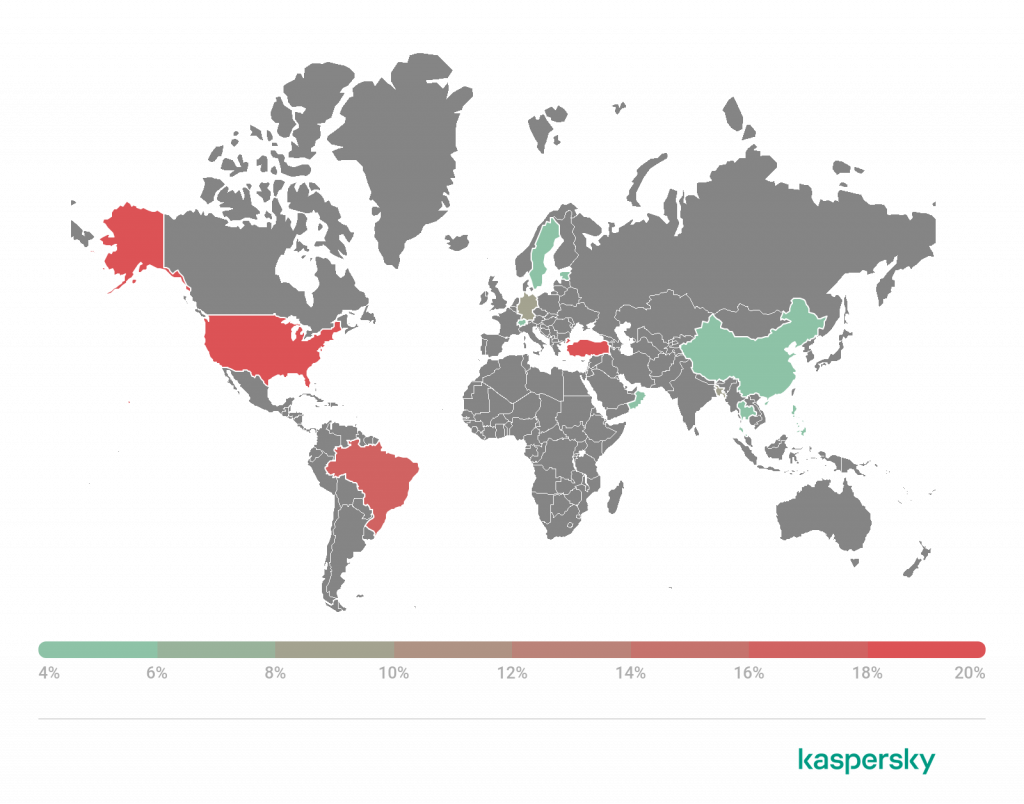

Yanluowang ransomware: how to recover encrypted files

The name Yanluowang is a reference to the Chinese deity Yanluo Wang, one of the Ten Kings of Hell. This ransomware is relatively recent. We do not know much about the victims, although data from the Kaspersky Security Network indicates that threat actor has carried out attacks in the US, Brazil, Turkey and a few other countries.

The low number of infections is due to the targeted nature of the ransomware: the threat actor prepares and implements attacks on specific companies only.

Our experts have discovered a vulnerability that allows files to be recovered without the attackers’ key — although only under certain conditions — with the help of a known-plaintext attack. This method overcomes the encryption algorithm if two versions of the same text are available: one clean and one encrypted. If the victim has clean copies of some of the encrypted files, our upgraded Rannoh Decryptor can analyze these and recover the rest of the information.

There is one snag: Yanluowang corrupts files slightly differently depending on their size. It encrypts small (less than 3 GB) files completely, and large ones, partially. So, the decryption requires clean files of different sizes. For files smaller than 3 GB, it is enough to have the original and an encrypted version of the file that are 1024 bytes or more. To recover files larger than 3 GB, however, you need original files of the appropriate size. However, if you find a clean file larger than 3 GB, it will generally be possible to recover both large and small files.

Ransomware TTPs

In June, we carried out an in-depth analysis of the TTPs (tactics, techniques and procedures) (TTPs) of the eight most widespread ransomware families: Conti/Ryuk, Pysa, Clop, Hive, Lockbit2.0, RagnarLocker, BlackByte and BlackCat. Our aim was to help those tasked with defending corporate systems to understand how ransomware groups operate and how to protect against their attacks.

The report includes the following:

- The TTPs of eight modern ransomware groups.

- A description of how various groups share more than half of their components and TTPs, with the core attack stages executed identically across groups.

- A cyber-kill chain diagram that combines the visible intersections and common elements of the selected ransomware groups and makes it possible to predict the threat actors’ next steps.

- A detailed analysis of each technique with examples of how various groups use them, and a comprehensive list of mitigations.

- SIGMA rules based on the described TTPs that can be applied to SIEM solutions.

Ransomware trends in 2022

Ahead of the Anti-Ransomware Day on May 12, we took the opportunity to outline the tendencies that have characterized ransomware in 2022. In our report, we highlight several trends that we have observed.

First, we are seeing more widespread development of cross-platform ransomware, as cybercriminals seek to penetrate complex environments running a variety of systems. By using cross-platform languages such as Rust and Golang, attackers are able to port their code, which allows them to encrypt data on more computers.

Second, ransomware gangs continue to industrialize and evolve into real businesses by adopting the techniques and processes used by legitimate software companies.

Third, the developers of ransomware are adopting a political stance, involving themselves in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

Finally, we offer best practices that organizations should adopt to help them defend against ransomware attacks:

- Keep software updated on all your devices.

- Focus your defense strategy on detecting lateral movements and data exfiltration.

- Enable ransomware protection for all endpoints.

- Install anti-APT and EDR solutions, enabling capabilities for advanced threat discovery and detection, investigation and timely remediation of incidents.

- Provide your SOC team with access to the latest threat intelligence.

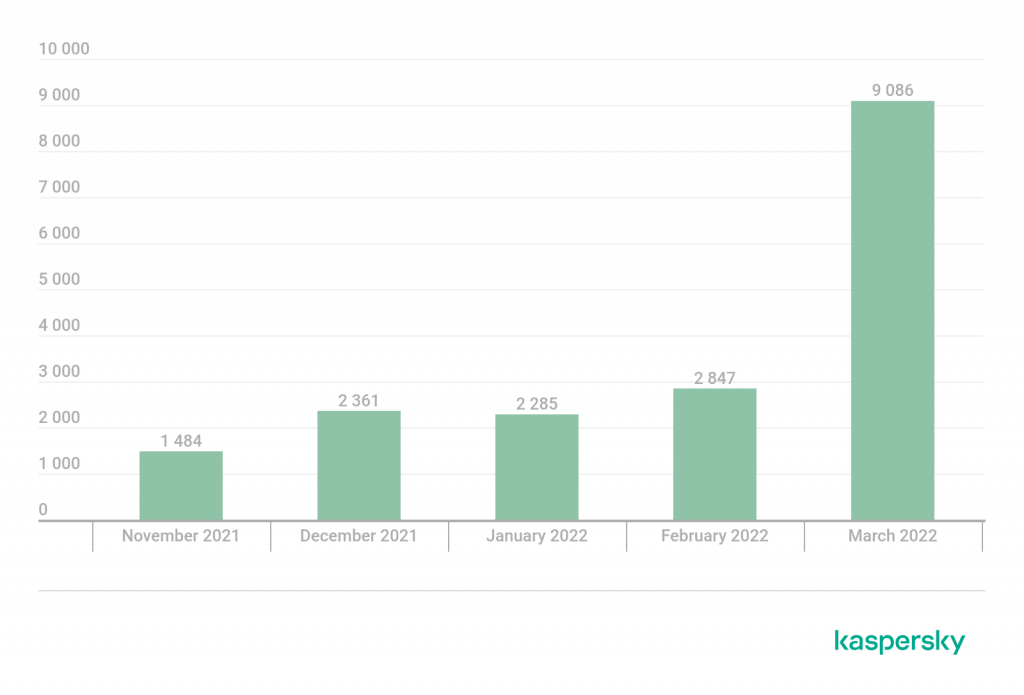

Emotet’s return

Emotet has been around for eight years. When it was first discovered in 2014, its main purpose was stealing banking credentials. Subsequently, the malware underwent numerous transformations to become one of the most powerful botnets ever. Emotet made headlines in January 2021, when its operations were disrupted through the joint efforts of law enforcement agencies in several countries. This kind of “takedowns” does not necessarily lead to the demise of a cybercriminal operation. It took the cybercriminals almost ten months to rebuild the infrastructure, but Emotet did return in November 2021. At that time, the Trickbot malware was used to deliver Emotet, but it is now spreading on its own through malicious spam campaigns.

Recent Emotet protocol analysis and C2 responses suggest that Emotet is now capable of downloading sixteen additional modules. We were able to retrieve ten of these, including two different copies of the spam module, used by Emotet for stealing credentials, passwords, accounts and emails, and to spread spam.

You can read our analysis of these modules, as well as statistics on recent Emotet attacks, here.

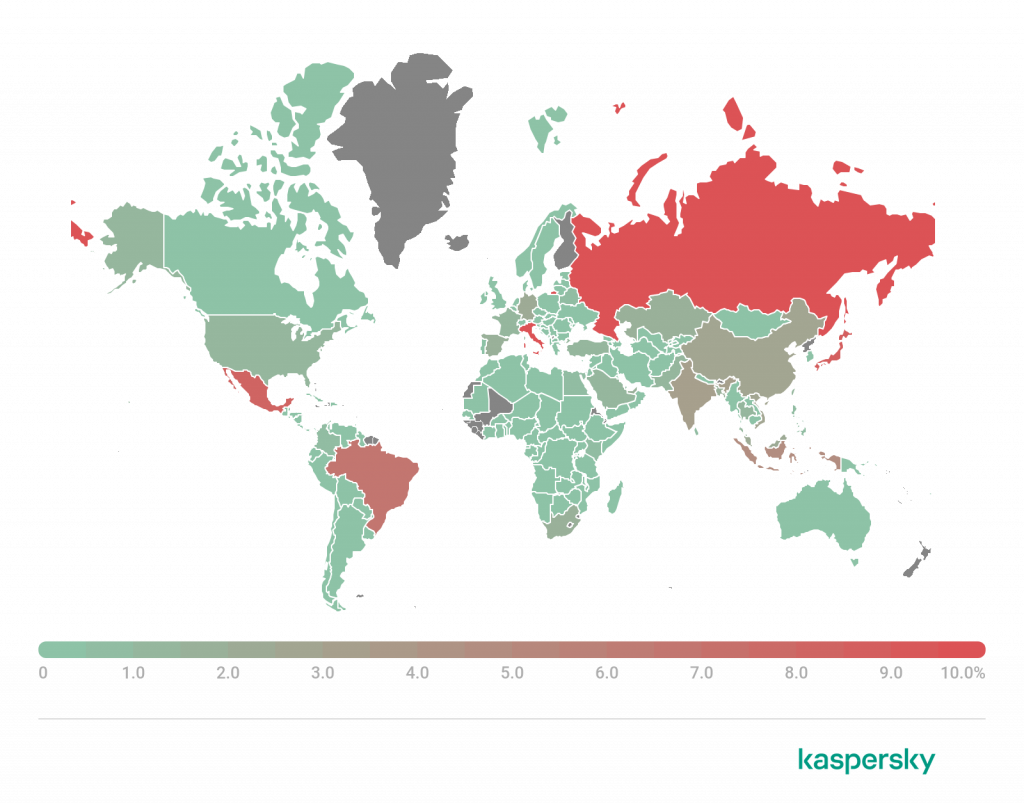

Emotet infects both corporate and private computers all around the world. Our telemetry indicates that in the first quarter of 2022, targeted: it mostly targeted users in Italy, Russia, Japan, Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, India, Vietnam, China, Germany and Malaysia.

Moreover, we have seen a significant growth in the number of users attacked by Emotet.

Mobile subscription Trojans

Trojan subscribers are a well-established method of stealing money from people using Android devices. These Trojans masquerade as useful apps but, once installed, silently subscribe to paid services.

The developers of these Trojans make money through commissions: they get a cut of what the person “spends”. Funds are typically deducted from the cellphone account, although in some cases, these may be debited directly to a bank card. We looked at the most notable examples that we have seen in the last twelve months, belonging to the Jocker, MobOk, Vesub and GriftHorse families.

Normally, someone has to actively subscribe to a service; providers often ask subscribers to enter a one-time code sent via SMS, to counter automated subscription attempts. To sidestep this protection, malware can request permission to access text messages; where they do not obtain this, they can steal confirmation codes from pop-up notifications about incoming messages.

Some Trojans can both steal confirmation codes from texts or notifications, and work around CAPTCHA: another means of protection against automated subscriptions. To recognize the code in the picture, the Trojan sends it to a special CAPTCHA recognition service.

Some malware is distributed through dubious sources under the guise of apps that are banned from official stores, for example, masquerading as apps for downloading content from YouTube or other streaming services, or as an unofficial Android version of GTA5. In addition, they can appear in these same sources as free versions of popular, expensive apps, such as Minecraft.

Other mobile subscription Trojans are less sophisticated. When run for the first time, they ask the user to enter their phone number, seemingly for login purposes. The subscription is issued as soon as they enter their number and click the login button, and the amount is debited to their cellphone account.

Other Trojans employ subscriptions with recurring payments. While this requires consent, the person using the phone might not realize they are signing up for regular automatic payments. Moreover, the first payment is often insignificant, with later charges being noticeably higher.

You can read more about this type of mobile Trojan, along with tips on how to avoid falling victim to it, here.

The threat from stalkerware

Over the last four years, we have published annual reports on the stalkerware situation, in particular using data from the Kaspersky Security Network. This year, our report also included the results of a survey on digital abuse commissioned by Kaspersky and several public organizations.

Stalkerware provides the digital means for a person to secretly monitor someone else’s private life and is often used to facilitate psychological and physical violence against intimate partners. The software is commercially available and can access an array of personal data, including device location, browser history, text messages, social media chats, photos and more. It may be legal to market stalkerware, although its use to monitor someone without their consent is not. Developers of stalkerware benefit from a vague legal framework that still exists in many countries.

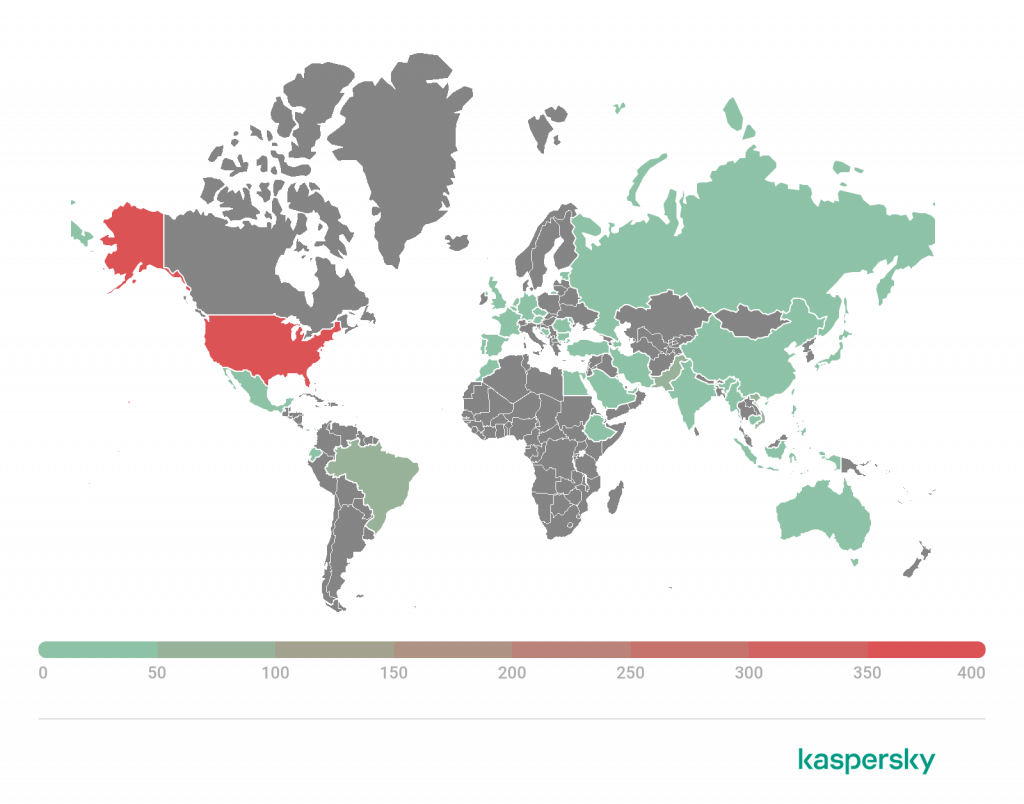

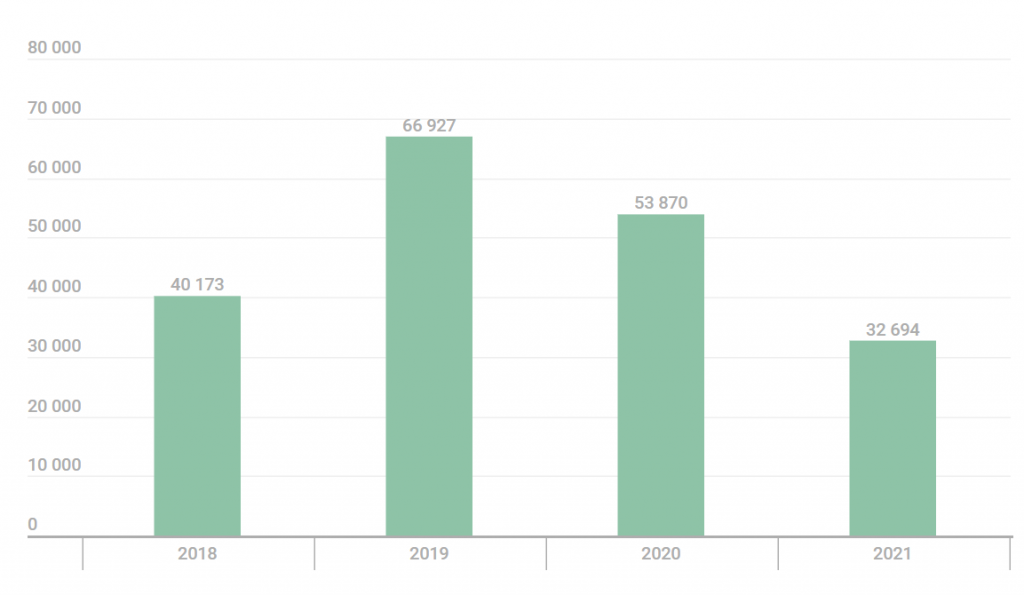

In 2021, our data indicated that around 33,000 people had been affected by stalkerware.

The numbers were lower than what we had seen for a few years prior to that. However, it is important to remember that the decrease of 2020 and 2021 occurred during successive COVID-19 lockdowns: that is, during conditions that meant abusers did not need digital tools to monitor and control their partners’ personal lives. It is also important to bear in mind that mobile apps represent only one method used by abusers to track someone — others include tracking devices such as AirTags, laptop applications, webcams, smart home systems and fitness trackers. KSN tracks only the use of mobile apps. Finally, KSN data is taken from mobile devices protected by Kaspersky products: many people do not protect their mobile devices. The Coalition Against Stalkerware, which brings together members of the IT industry and non-profit companies, believes that the overall number of people affected by this threat might be thirty times higher — that is around a million people!

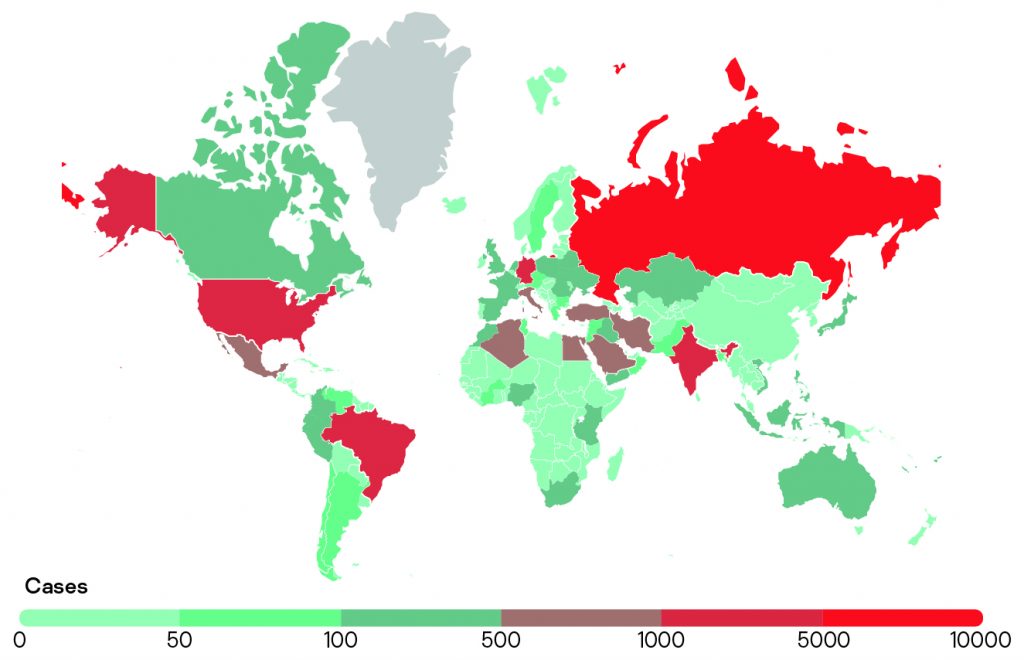

Stalkerware continues to affect people across the world: in 2021, we observed detections in 185 countries or territories.

Just as in 2020, Russia, Brazil, the US and India were the top four countries with the largest numbers of affected individuals. Interestingly, Mexico had fallen from fifth to ninth place. Algeria, Turkey and Egypt entered the top ten, replacing Italy, the UK and Saudi Arabia, which were no longer in the top ten.

We would recommend the following to reduce your risk of being targeted:

- Use a unique, complex password on your phone and do not share it with anyone.

- Try not to leave your phone unattended; and if you have to, lock it.

- Download apps only from official stores.

- Protect your mobile device with trustworthy security software and make sure it is able to detect stalkerware.

Remember also that if you discover stalkerware on your phone, dealing with the problem is not as simple as just removing the stalkerware app. This will alert the abuser to the fact that you have become aware of their activities and may precipitate physical abuse. Instead, seek help: you can find a list or organizations that can provide help and support on the Coalition Against Stalkerware site.