Top crypto VCs are constantly touting the potential of video games as one of the most compelling use cases for blockchain technology. Andreessen Horowitz partner Arianna Simpson, for example, who led the firm’s investment in crypto game Axie Infinity, has given countless interviews citing the play-to-earn model as a key catalyst to attracting “hundreds of millions” of people into web3.

Axie, the highest-profile play-to-earn video game, suffered one of the largest crypto heists to date this past March when North Korean hacker organization Lazarus Group drained ~$625 million from the game’s Ethereum-based Ronin sidechain. Since then, crypto markets as a whole have gone through a severe price downturn and a subsequent recovery in the past month. So where does that leave web3 gaming and the play-to-earn business model?

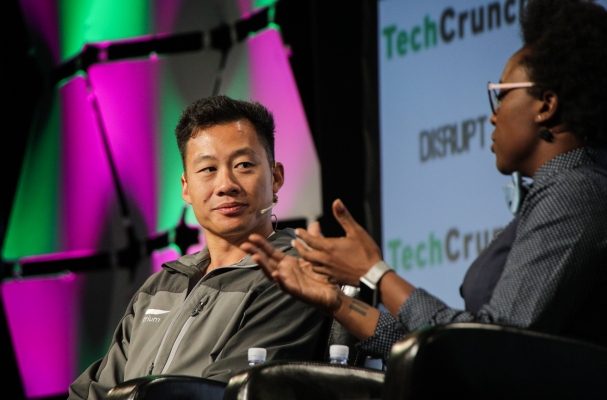

TechCrunch talked to Justin Kan, co-founder of Twitch and more recently, Solana-based gaming NFT marketplace Fractal, to get his thoughts on what it will take for this subsector of web3 to live up to the hype. Kan said that web3 gaming has a long way to go — while there are about 3 billion gamers in the world, including those who play mobile games, he noted, far fewer have bought or interacted with any sort of blockchain-based gaming asset.

Kan sees this gap as an opportunity for blockchain technology to fundamentally change how video game studios operate.

“I think the idea of creating digital assets, and then taxing everyone for all the transactions around them is a good model,” Kan said.

In some ways, web3 gaming was been built in response to the success of games such as Fortnite that were able to unlock a lucrative monetization path for gaming studios through micro-transactions from users buying custom items such as outfits and weapons. Web3 game developers hope to take that vision a step further by enabling players to take those custom digital assets between different games, turning gaming into an interoperable, immersive ecosystem, Kan explained.

Kan has made around 10 angel investments in web3 gaming startups, including in the studio behind NFT-based shooter game BR1: Infinite Royale, he said. Still, he admitted that building this interoperable ecosystem, which he sees as the future of video games overall, doesn’t technically require blockchain technology at all.

“Blockchain is just the way that it’s going to happen, I think, because there’s a lot of cultural momentum around people equating blockchain with openness and trusting things that are decentralized on the blockchain.”

The vision of interoperability has yet to be realized in the traditional gaming world because many incumbent studios have been loathe to encourage third-parties to build on top of their APIs, Kan said. He attributed their reticence to an “innovator’s dilemma,” wherein large gaming companies with business models that already work are hesitant to take new risks.

Gamers, though, seem to value the openness and economic participation afforded by blockchain-based startups, Kan said. Still, he added, the appeal of an open gaming ecosystem is more about the principle of the matter than it is about making a living.

“I actually think that people equate NFTs and games with this play-to-earn model where people are making money and doing their job [by gaming], and I think that’s completely unnecessary,” Kan said.

“Having digital assets in your game can work and be valuable, even if nobody is making money and there’s no speculative appreciation or price appreciation on your assets,” he added.

It’s common for popular games to attract new development on top of their existing intellectual property. Kan shared the example of Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CSGO), a video game in which custom “skins” have sold for as much as $150,000 each.

“I funded a company that builds on top of the CSGO skins,” he said. “CSGO changed the rules about what was allowed and actually confiscated over a million dollars just from this company — so yeah, I don’t want to build on top of these non-open platforms anymore.”

Plenty of prominent studios disagree with Kan’s thesis that an open gaming ecosystem monetized through blockchain technology is the future of the video game industry. Minecraft, one of the most popular games of all time, made waves last month when it announced it would not support NFTs on its platform, citing concerns around the “speculative pricing and investment mentality” in web3 and arguing that NFTs would run counter to fostering an inclusive environment for players.

Despite that it drew the line at NFTs, Minecraft does currently make money off of micro-transactions on its in-game marketplace. The decision leaves in flux existing companies that were already selling Minecraft-based NFTs and developing play-to-earn games using its open source code.

Kan sees blockchain-based games as just a “more economically immersive” version of the marketplaces that already exist in video games. He doesn’t think users will flock to blockchain gaming just to make money, though.

“Play-to-earn was associated with people who are doing this kind of rote, menial work in third-world countries or developing countries,” Kan said. “I don’t particularly think the model is sustainable, so I think that interest will kind of subside.”

Instead, he thinks the growth in web3 gaming will be driven by developers building genuinely fun games on the blockchain rather than focusing on creating economic incentives under the play-to-earn paradigm.

“I think that web3 games are just being more open and saying, instead of this being a black market, we’re going to make this a real market and people’s economic participation is going to vary to different levels. There’s gonna be people who only play the game and never buy things with money. There’s gonna be some people who are making some side money because they’re really good at the game, and they’re getting some things in the game they’re selling [or trading].”

Kan predicts that the space will evolve similarly to how mobile gaming did, with a handful of startups taking off initially. Their success will inspire big gaming companies to leverage their existing IP to enter the fray “five years later,” despite their initial misgivings about the technology, he added.

Still, the nascent sector of blockchain gaming has miles to go before it can attract widespread attention.

“In order for this market to actually be big, it’s going to require normal people who want to play games for fun to play these games. That doesn’t exist yet. I think most of the market today is people who are crypto-native,” Kan said.